This article originally appeared in the October 2022 issue of Cross Pollination, the newsletter of the Halton Region Master Gardeners.

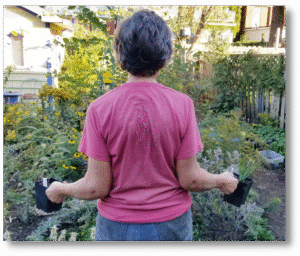

Late one evening in mid-September I was walking around my small urban garden with a plant in each hand, unaware that my husband was watching.

“Looking for a place to plant those?” he asked.

“Yup. I gotta get these in the ground before I run out of time.”

“You have a lot of new plants,” he remarked blandly.

“And they take a lot of time. Most of them are pot-bound, which means a lot of clipping and fussing” I explained, even though his comment was aimed at the expense, not the work, these new plants represented.

photo: Sean Hurley CC BY-NC-SA

I was holding three pots of hairy panic grass (Dichanthelium acuminatum var. fasciculatum), an unusual native species that I remember buying as an edging plant for an interesting contrast in texture to the usual leafy stuff. But that’s all I could remember without running upstairs to consult google or my spreadsheet. Sun or shade? Dry or moist? Conscious of the setting sun and the many plants in the queue, I plopped them in a convenient open space and stuck the marker. That would do until spring.

Introducing plants to my garden remains joyful and stress-free because, 27 years after starting out, I’m still doing the plunk-and-plop.

I’ve always been a collector, especially before I got into native plants, when I had plentiful land, great soil, ample time, and functional hips. My desire to grow all the plants has softened with age and tempered by, well, new realities. I look back with wistful fondness to those early years when plunk-and-plop gardening expressed the naive enthusiasm of someone who just loved growing things.

Back then, the Internet was not so huge and daunting. Facebook was a just a way to connect with distant friends. Whether we knew it or not, information on bulletin boards and chat groups was sketchy. Horticultural institutions had not figured out the purpose their “online presence” and reliable science-based information was hard to find, even if we were savvy enough to look for it.

Nowadays the Internet can be a paralyzing onslaught of information and opinion. Overwhelming is the word I hear a lot from novice gardeners. The charlatans promise quick-and-easy, the profit-seekers elbow and bellow, the seminar watch-list grows, the gurus and experts clamour for our eyeballs and clicks. For someone just starting out, it’s like a loud, tangled swamp on the first leg of their gardening journey.

If you’re stuck in the swamp, here’s what to do: plunk and plop. Just put those plants in the ground. It doesn’t matter so much where you put them. What’s important is that you pay attention to them. They, perhaps more than the Internet (but probably not books), will guide you on your gardening journey.

Being a plunk-and-plop gardener is part expedience (“this plant is bustin’ out and has to get in the ground right away”), part defiance (“no one tells me what/where/how/why to plant”), and part impatience (“I don’t have time for this.”)

These three tenets are the core curriculum of the plunk-and-plop school of gardening. Let’s take a closer look.

Expedience

No one can do things right all the time. But getting that plant out of the pot, and into the soil is the first step. Just plant it, no matter how imperfectly. Plunking plants is better than abandoning them on a hot patio while you get around to weeding the space, pruning the overhanging shrub, enlarging the planting bed, or fixing the hose. So fill up your watering can, pop those little guys out, tease the roots, dig a hole, water, plunk, and water again. Put the plant marker beside it. Then write in your journal (or spreadsheet or phone) what you did. You will need this information this winter as you research the plant and decide on a better home for it. Always keep in mind that plants can be moved, replaced, and replicated. Right now you’re not aiming for perfection—you’re just keeping that plant alive and out of misery for the short term.

Defiance

I’m not saying that expert advice is bad. But don’t let it paralyze you. If you balk at a Master Gardener telling you to get rid of all your oriental honeysuckle, miscanthus, vinca, goutweed, lily-of-the-valley, burning bush, ditch lily (and possibly lilac and rose-of-sharon too) remember that you can remove the bad guys and grow the good guys at the same time. Find a spot for a nursery bed (my English friend used to call this her “plunge bed”) and enjoy observing and caring for your babies while you kill invasives to make room for your new plants.

If necessary, have the courage to defy your neighbours. If you want vegetables in your front yard, or a native-plant garden with goldenrod, or a rain garden instead of a koi pond, just do it. Bucking the trend—or simply following your muse—can be a great motivator to do the research. Arm yourself with facts so the next time someone tries to unload some thugs, or suggests a homemade spray, or explains what you’re doing wrong, you can explain why you’re doing it your way. Understand the benefits of native plants, biodiversity, ecological function, water retention, and all the other good reasons you have. Remember this is your garden. It’s your space to create, restore, showcase, and enjoy.

Impatience

If you’re an older person just setting out on your gardening journey, you may balk at advice to wait and observe. For example, it’s wise to wait a year in a new space to learn the soil, the sun patterns, and existing plants. You may be told to start with the “bones” (trees and shrubs) and progress, over several seasons, to the “pretties” (flowers). And if your yard has accumulated a lot of invasive plants, it may take several years to remove them.

Here’s how the plunk-and-plop approach can help impatient gardeners: go ahead and plant your pretties now but move them later. Each year is a new creative opportunity and those first impulsive plunkings will become a source of seed and divisions for bonus plants at no cost.

The old adage about planting a tree that your grandchildren will enjoy is more prescient than ever. We simply must have patience with trees. But certain shrubs and vines, on the other hand, are great options for impatient gardeners. Consider other quick ways to achieve a leafy-green canopy: cover a pergola with a native clematis (C. virginiana); build a shade structure with a “green roof” lined with cascading perennials; or plunk down a big canvas canopy with hanging baskets all around.

Being impatient is no excuse for carelessness, though. The plunk-and-plop school of gardening is still a school, so you need to write things down and (eventually) do your research. A journal or a spreadsheet will do, with a digital option having the advantage of being searchable by keyword. Even in October when your hands are cold and you’re looking to plunk a “pretty” before the frost hits, write it down. No matter how often you repeat the name of that plant, by April your memory will be fog. Send your garden buddy an email telling them about the great Blasteromus bazookinus you plunked today, so at least there is a record of it. At the very least, put some sticks or rocks in a circle around it so you don’t accidently weed it out in the spring.

Do we ever arrive?

I sometimes wish my gardening journey hadn’t lingered so long on the pretty flowers and botanical oddities. But gardening with minimal constraints was an enviable freedom—a “cushy life” as one neighbour put it. Despite having plans in my head, my first gardens simply evolved as new plants were grown, purchased, or found on my doorstep. My gardening journey welcomed almost anything that came my way. It was a wonderful way to learn. It’s what we used to mean by “self taught.”

So now, as I wander, a plant in each hand, through my small urban garden with its new cadre of challenges, I’m wistfully reminded of those years of youthful exuberance. There is so little time left. Even less space. These plants need to get in the ground right away. Plunk. Plop.